For a quarter of a century Christian Vander's Magma have been engaged in a musical quest that frames visions of apocalypse and redemption with bulldozing experimental fusion. In this exclusive interview, Vander talks to Paul Stump about invented languages, John Coltrane, children's songs and the striving towards the light.

I'm

sitting in a tiny theatre in Paris waiting to see my first performance by

(and conduct my first interview with) Christian Vander. Magma. The name of

the group that Vander has led, on and off, for much of the last quarter of

a century is an appropriate tag for his music; suggestive of seismic activity,

volcanic eruptions, torrential flows of molten lava cooling into huge edifices

of solid rock. In those 25 years, Vander has recorded the most towering and

ambitious music ever to be damned by the label 'Progressive rock'. But the

audience at this particular Paris show isn't made up of the acid-casualties,

Kobaïan kompletists and fortysomething Prog nostalgia freaks one might

expect. Instead, I'm surrounded by sickeningly winsome under-fives. Vander's

latest project, A Tous Les Enfants, isn't another brontosaurial cosmic epic.

It is, as the title suggests, a show for kids. "I don't just write Magma-type

stuff, you know" he says, fixing me with his spookily intense stare.

But isn't this a bit offbeat, even for you, Christian? "No," he

says mildly. "Ali my music has at its heart a logical progression. I

just write it for different occasions. There are various aspects of it. At

the moment I just happen to be writing for children. And it's a real pleasure

performing to them..."

I'm

sitting in a tiny theatre in Paris waiting to see my first performance by

(and conduct my first interview with) Christian Vander. Magma. The name of

the group that Vander has led, on and off, for much of the last quarter of

a century is an appropriate tag for his music; suggestive of seismic activity,

volcanic eruptions, torrential flows of molten lava cooling into huge edifices

of solid rock. In those 25 years, Vander has recorded the most towering and

ambitious music ever to be damned by the label 'Progressive rock'. But the

audience at this particular Paris show isn't made up of the acid-casualties,

Kobaïan kompletists and fortysomething Prog nostalgia freaks one might

expect. Instead, I'm surrounded by sickeningly winsome under-fives. Vander's

latest project, A Tous Les Enfants, isn't another brontosaurial cosmic epic.

It is, as the title suggests, a show for kids. "I don't just write Magma-type

stuff, you know" he says, fixing me with his spookily intense stare.

But isn't this a bit offbeat, even for you, Christian? "No," he

says mildly. "Ali my music has at its heart a logical progression. I

just write it for different occasions. There are various aspects of it. At

the moment I just happen to be writing for children. And it's a real pleasure

performing to them..."

The mythology

that has built up around Vander, of a grim, obsessive paramilitary, is an

apt counterpoint to the phantasmagoria he has catalogued in his work. But

like all myths, it admixes a little more fiction than fact. And despite two

and a half decades of unrelenting media enmity of the sort that vilifies pre-punk

70s rock (and groups like Magma in particular) as a kind of giant historical

aberration, the myth still has a following. The response to a brief Magma

namecheck in The Wire last year indicated that it wasn't only the Ambient

rediscoveries of Krautrock (so admirably outlined in these pages by Julian

Cope in The Wire 130) that warranted a journey back in time and space : it

was time to reopen the files on another Euro-rock legend long since fingered

as one of pop's ultimate actes noires.

"Ask me anything you want," he says. "I'll try and help."

But it isn't easy; the myth gets in the way. I expected to meet a wild-eyed,

polysyllabic fount of Gallic enigmas; but the hirsute Vander, for all his

musical excesses, is a remarkably reticent man and tends towards shy generalisations

in his answers. "I don't understand where everyone gets this image of

me from," he complains.

Maybe from the score-or-so albums, recorded under various pseudonyms (Magma

simply being the best known), with which Vander has produced some of Europe's

most relentlessly bizarre popular music. While 'popular' may not mean what

it once did to Vander (and Magma were very big in Europe in the 70s), his

esoteric odyssey continues.

Magma's

formation, in 1969, coincided with the belated consecration of a French rock

culture. Fertilised more by indigenous folk and parlour sang as well as the

musics of Eastern and Southern European immigrants, French pop songs only

paid comparatively token homage to the jazz and blues elements so central

to Anglophone pop, and it was this that the roisterous bouleversements of

60s youth culture sought to subvert in their music. But in discovering The

Beatles, Jimi Hendrix and Pink Floyd, putative French rockers (the better

ones, in any case) found the traditional bonds of their musical upbringing

more of an inspiration than an encumbrance. Additionally, there was French

jazz (largely, but not entirely, independent of the French chanson heritage)

to draw on as well. And so, as Situationism sought to dismantle the Spectacle,

the French rock scene set about rearranging the pieces in some stunning musical

hybrids all but unknown to British audiences : Ange (Brel versus Genesis),

Barricade (Zazou 'n' Racaille before the event), Etron Fou Leloublan (Folk

Rock In Opposition), and, inevitably, Magma As Germany's technocratic post-war

miracle and resultant urban alienation fed the futuristic, hardware-orientated

inspiration of the Krautrock groups, se the multicultural vibrancy and instability

of 60s Paris informed French rock's own Year Zero of 1969. But to Vander's

reckoning, only one year counts. "1967," he says. "The year

John Coltrane died. It seemed to me that afterwards, it was as though music

had to try to start all over again. Someone had to pick up the pieces, go

on searching in the way that he had. Nobody could match him, but people could

pick up the flame. It was almost impossible for anyone to do anything new

after Coltrane, but you had to try, try to find other new directions. Sa that's

what I tried to do with Magma. I was a bit young at the time, but…"

He tried anyway. "Sure, things were happening in 1968," he says

now. "I just tried to contribute what I could on the musical front"

Magma's

formation, in 1969, coincided with the belated consecration of a French rock

culture. Fertilised more by indigenous folk and parlour sang as well as the

musics of Eastern and Southern European immigrants, French pop songs only

paid comparatively token homage to the jazz and blues elements so central

to Anglophone pop, and it was this that the roisterous bouleversements of

60s youth culture sought to subvert in their music. But in discovering The

Beatles, Jimi Hendrix and Pink Floyd, putative French rockers (the better

ones, in any case) found the traditional bonds of their musical upbringing

more of an inspiration than an encumbrance. Additionally, there was French

jazz (largely, but not entirely, independent of the French chanson heritage)

to draw on as well. And so, as Situationism sought to dismantle the Spectacle,

the French rock scene set about rearranging the pieces in some stunning musical

hybrids all but unknown to British audiences : Ange (Brel versus Genesis),

Barricade (Zazou 'n' Racaille before the event), Etron Fou Leloublan (Folk

Rock In Opposition), and, inevitably, Magma As Germany's technocratic post-war

miracle and resultant urban alienation fed the futuristic, hardware-orientated

inspiration of the Krautrock groups, se the multicultural vibrancy and instability

of 60s Paris informed French rock's own Year Zero of 1969. But to Vander's

reckoning, only one year counts. "1967," he says. "The year

John Coltrane died. It seemed to me that afterwards, it was as though music

had to try to start all over again. Someone had to pick up the pieces, go

on searching in the way that he had. Nobody could match him, but people could

pick up the flame. It was almost impossible for anyone to do anything new

after Coltrane, but you had to try, try to find other new directions. Sa that's

what I tried to do with Magma. I was a bit young at the time, but…"

He tried anyway. "Sure, things were happening in 1968," he says

now. "I just tried to contribute what I could on the musical front"

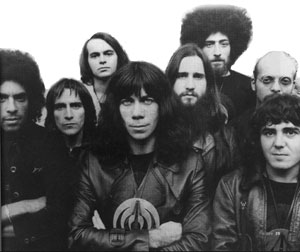

Magma may

not have been the most subversive of French groups but they were certainly

the most arresting. Their first album (Magma, 1970) set the tone, a double

LP of explosive and frequently cacophonous semi-improvised rock, bulldozed

on by Vander's astonishing drumming and Francis Moze's apocalyptic bass playing.

Magma, the relation in music of a vast interplanetary voyage, was the first

part of a multi-album extravaganza, Theusz Hahmtaahk, which set out to chronicle

the death of Earth and the migration of humanity to Vander's invented planet

Kobaïa and the ultimate return of the all-powerful deity Ptäh. All

this was (is) related in Vander's own Kobaïan language (which took its

'vocabulary' partly from Leone Thomas's scat-yodelling vocal style), and declaimed

either by the steely-brilliant voice of Vander's wife Stella, the powerhouse

singer Klaus Blasquiz or massive quasi-operatic choruses. (As Magma expert

Michael Draine has observed, "The abstraction provided by the Kobaïan

verse seems to inspire Magmas singers to heights of emotional abandon rarely

permitted by conventional lyrics.") "It wasn't at all easy to compose

for forces like that at first," admits Vander now. "I was only in

my early twenties. But it was the only way to say what I wanted to say…"

What followed was a voyage appropriately as vast as that recounted on Magma.

The music didn't change much, but then it didn't have to. It was a towering

bricolage of styles; unique, at least in terms of the rock tradition Magma

were shoehorned into. Although the metric propulsion of Vander and Moze recalled

contemporary jazz rock, the music was never of the cheesecloth-shirted, funkily

suburban kind that would have attracted major record labels. No Corea-style

whimsy here; no McLaughlinesque lushness: instead, an apocalypse of massively

amplified collective improvisation. "Jazz is very important in my music,"

says Vander. "I listened to all the greats - thanks to my mother. We

moved to Paris when I was very young and I was introduced to the Parisian

club scene in the late 50s and early 60s. I was lucky - I was able to see

and hear wonderful musicians. Great drummers: Max Roach, Elvin Jones, Kenny

Clarke, Tony Williams later on. And Chet Baker gave me my first drum kit."

Vander

incorporated Western classical elements too, but not the grade five Bach transcriptions

of most Prog rock. "Wagner, of course; everyone always mentions Wagner,"

he smiles. "But that's largely to do with scale and structure. I was

also very receptive to more contemporary composers: Stravinsky [hear how Vander

uses rhythm as a basis for melody]; Bartok, too [ditto the shrill, Eastern

European folk influences]." Coltrane's influence was echoed in long stretches

of music reserved for fast and hard-blowing soloists that also recalled Ornette

Coleman. While other musicians who had come to fusion via circuitous routes

(R&B, classical training, jazz studies, genre musics) studied sitar notation

or buddied up to Sri Chinmoy, Vander was into Transylvanian harmolodics; with

the cosmic angle thrown in, it was like a rocked-up take on Sun Ra's Myth

Arkestra. But nobody ever accused Sun Ra of pretentiousness the way they've

mercilessly pilloried Vander.

Vander

incorporated Western classical elements too, but not the grade five Bach transcriptions

of most Prog rock. "Wagner, of course; everyone always mentions Wagner,"

he smiles. "But that's largely to do with scale and structure. I was

also very receptive to more contemporary composers: Stravinsky [hear how Vander

uses rhythm as a basis for melody]; Bartok, too [ditto the shrill, Eastern

European folk influences]." Coltrane's influence was echoed in long stretches

of music reserved for fast and hard-blowing soloists that also recalled Ornette

Coleman. While other musicians who had come to fusion via circuitous routes

(R&B, classical training, jazz studies, genre musics) studied sitar notation

or buddied up to Sri Chinmoy, Vander was into Transylvanian harmolodics; with

the cosmic angle thrown in, it was like a rocked-up take on Sun Ra's Myth

Arkestra. But nobody ever accused Sun Ra of pretentiousness the way they've

mercilessly pilloried Vander.

It was popular pretension, though; Magma's marathon concerts drew considerable

crowds and the group stormed the 1973 Newport Jazz Festival, even bringing

some attention from the traditionally parochial UK. "The French reaction

to Magma was, initially, one of complete surprise. At the quality, for a start,"

he grins. "They didn't believe Frenchmen could play like that. And they

found the music too violent, too aggressive… too hard." Surprisingly

(and a little ingenuously) he denies any native influence. "I don't think

there's anything French about my music [it's always 'my music'] because my

roots are Eastern European. [There are many Hungarian and Romanian elements

in the Kobaïan 'tongue'.]. You can hear that in the music. France hardly

comes into it at all. Perhaps a bit, but net consciously."

What is surprising about Vander's resolutely monumental and ritualistic music

is its abrasiveness and intensity. Hhaï: Live, which documents a 1975

Magma live performance, is perhaps the best recorded example of the group's

sound. The music often remains largely tonal, lavish in conception, and symphonically

structured into sweeping sections. Although it lacks the improvisational jouissance

of a Zappa or Hendrix at full tilt, the energy level is staggering, capsizing,

in a unique way, conventional notions of how such opulent musical resources

should be treated. Moreover, there are no Floydian bliss-outs or synthesized

sybaritism. ("I'm not keen on too many electronic instruments,"

says Vander. "They're not always very practical.")

What about the death-defying balance of the composed and improvised in his

music? Here Vander is a bit vague. "There are some themes I put together

strictly for group working out, for solo or group improvisations. Others are

wholly structured. But if anyone wants to contribute anything…"

He shrugs, giving the lie to the popular notion of him as Nemoid control freak.

Throughout

the 70s, Magmas pre-eminence brought French musicians flocking. Sidemen came

and vent at will (one of the mort notable being the brilliant bassist Jannick

Top), forming and dissolving their own Vander-influenced groups (Zao, Weidorje).

There were even links with avant garde noisemakers Heldon, Magma's only real

rival in the French underground, and other darkside Eurorockers such as Art

Zoyd and Univers Zero admitted a debt to Vander's vision. Even today, younger

groups attempting to rewrite the European Prog tradition - Xaal (France),

Anekdoten (Sweden) - freely cite his influence.

Magma fell dormant in 1984, but it meant little; the music was always Vander's

(he coined the term 'zeuhl music' to describe the canon he was creating).

"Magma was just a name I used for it. I wanted to compose and play on

different levels. I started up a jazz trio [to act as an outlet for his still-obsessive

love of Coltrane], and also I started up Offering - a bit controversially."

Offering a percussion and voice-dominated ensemble in the Magma musical tradition,

showed signs of jettisoning the chugging rock pulses which had underpinned

Vander's music for so long. Now it seemed as if he was willing to let some

light into the music, learning to use space as an enriching compositional

device rather than fitting subject matter for a concept album.

Does he take much notice of contemporary musical developments? "Net very

much," he sighs. "I never listen to the radio. I don't watch TV.

Mind you, I never did listen to much else. I'm often too busy with my own

work. I try to keep up with what's happening in jazz; a lot of my musicians

are active in that sphere, but that's about it. There's also a real problem

for creative music now. There are so many schools, so many genres of music,

it's getting difficult to achieve anything new. It's almost like we have to

unlearn in order to rediscover ways of seeing and doing." It's much the

same when I ask him how he perceives his audience: are his followers young

or old? "I don't know!" He laughs this time. "I'm told there's

many young people in the audience still, which is great. But when I get out

on stage behind the drums, I just play. I never look - I just want to do my

best. Now, playing in front of kids - that's different. They're so receptive."

Christian

Vander is still as hyperactive as his best music. One current project, Les

Voix Du Magma, a 12 piece featuring seven vocalists and five instrumentalists

is to be augmented soon by an orchestral project ("Anything between 50

and 150 musicians"), incorporating a transcription of the whole of Theusz

Hahmtaahk. "Originally, I'd wanted to do Theusz Hahmtaahk for orchestra,

but it was impossible to put together in the 70s. Now, who knows? In fact,

I'd love to do more with the orchestra, full stop. But it's difficult. What

I need is a Mad King Ludwig to finance me!" he says, referring to Wagner's

great benefactor.

Christian

Vander is still as hyperactive as his best music. One current project, Les

Voix Du Magma, a 12 piece featuring seven vocalists and five instrumentalists

is to be augmented soon by an orchestral project ("Anything between 50

and 150 musicians"), incorporating a transcription of the whole of Theusz

Hahmtaahk. "Originally, I'd wanted to do Theusz Hahmtaahk for orchestra,

but it was impossible to put together in the 70s. Now, who knows? In fact,

I'd love to do more with the orchestra, full stop. But it's difficult. What

I need is a Mad King Ludwig to finance me!" he says, referring to Wagner's

great benefactor.

Vander stresses that he is keen to emphasise his personality in his music,

and there's certainly little chance of him ever hiding his light under a bushel.

For example, A Tous Les Enfants might have been conceived as a performance

for children, but the Paris show contained systems music, MOR passages, ballads,

sampled atmospheres, clowning and a closing section which turned a traditional

French lullaby into a nightmarish, polytonal Gregorian invocation.

Vander seems to adhere not just to Coltrane's musical vision but also his

conception of music as something intrinsically transcendent. Certainly this

notion seems to inform his fanatical missionary zeal, and his idealist striving

for absolutes burns as brightly as ever: when I asked him about A Tous Les

Enfants, the first thing he said vas, "It's vital to get across to children

that they are the future, and that they should be valued for that reason.

"A Tous Les Enfants," he continues, "is a work that banishes

all contradictions - wealth and poverty, happiness and sadness. I dislike

such things. Kobaïan, the language, is meant to eliminate ambiguities

in human expression, the oppositions which divide humanity. My message is

a positive one: life, the striving towards the light."

The whole concept of Kobaïa, it seems, is less a mere tool for communicating

ideas or a planetary imagining of Vander's distant post; it's an entire holistic

mindset (the striking Kobaïa logo which Vander wears perennially around

his neck is an example).

"Of course I will go on working in Kobaïan," he says. (For

the record, A Tous Les Enfants is in French.) "I invented Kobaïan

because French just wasn't expressive enough. Either for the story or for

the sound of the music." In a sense, then, Kobaïan is something

of a red herring - the new language Vander invented wasn't just one of words,

but of music also: in his world, the two are inseparable.

The music

of Christian Vander is no longer at the cutting edge. If he's aware of that

- and one gets the impression that he is - he doesn't care. Because to be

at the cutting edge means being a constituent of something else, and that's

one thing Vander's music has never been.

Vander doesn't march to the beat of a different drummer. He is a different

drummer. And that's surely something worth celebrating, irrespective of what

language you use.

Paul Stump

Some records: Magma (aka Kobaïa) (Seventh REX IV/V); 1001 Centigrade

(Seventh REX VI), Mekanïk Destruktïw Kommandöh (Seventh REX

VII); Wurdah Ïtah (Seventh REX IX); Köhntarkösz (Seventh REX

VIII); Hhaï/Live (Seventh REX X/IX); Üdü Wüdü (Seventh

REX XII), Attahk (Seventh REX XIII).

In addition to the above releases, most of Christian Vander's recordings are now available on the Seventh label and are distributed in the UK by Harmonia Mundi. For more information contact Seventh Records, 101 Avenue Jean Jaures, 93800 Epinay-sur-Seine, France. The Magma fanzine, Ork Alarm!, can be reached at PO Box 419, Erith, Kent DA8 1 TE. Special thanks to Stephen Farmer, Paul Mummery, Christian Vander, Pascal Zelcer, Christelle Chaigné and Trevor Manwaring.

Source : The Wire - Issue 137

- July 1995

Zeuhl Merci : Jean-Marc Delville

|

|

|

|

Zïha Daniel / akoustikus pour le document